Verizon is one of the big three American phone companies. After the original AT&T was trustbusted into seven parts in the 80s, some of them re-consolidated and rebranded as the company we know today. It successfully made the transition to wireless services as mobile phones exploded in the Aughts, but facing an identity crisis in the 2010s, Verizon made some dubious acquisitions that ended in their resale just last year. Just what happened to Verizon’s media wing?

Paradigm Shift

The period from 12/31/2005 to 12/31/2015 was an upward one for Verizon. Operating Cash Flows in 2005 were $22 million. By the end of 2015, OCF had risen to $38.9 million, a CAGR of 5.85%, and the company began a streak of annual dividend increases that remains uninterrupted. The stock price (seen above) followed the profits, starting at $13 in late 2005 and reaching about $35 in 2015.

The transformation of phone services in this time was undeniable. We had a society in which phone use was mainly wired. Wireless was a paradigm shift, but it was not an immediate one. We all remember the commercials in which providers bragged about allowing “rollover minutes.” By 2015, such a commercial would have been marketing suicide and an admission of an inferior product.

Verizon played a major role in this transformation, even wading through the Great Recession to do it. It was the mark of a wonderful business, and with the paradigm shift complete, improvements in phone services would only come on the margins, on a wider geography of coverage and faster service. Otherwise, the biggest beasts were already slain, and so this telecom perhaps wanted to do more than rest on its laurels.

Easy Prey

Two companies came under Verizon’s watch by this point: AOL and Yahoo. Both of them have similar stories. AOL was originally the dominant player in providing Internet service in the 90s. For many of us, AOL was how we first used the Internet and can remember the dial-up sounds every time we went online. Iconic to a fault, it represented paying for slowness. Broadband killed AOL as we entered the New Millennium. The company merged with Time Warner in 2001 and began focusing on adjacent services like email and instant messaging.

The merger didn’t materialize well. Its services were always second-best to something else. In 2009, the company spun off from Time Warner with new management and tried to make it as a digital media company. Of course, this did not end the trend. YouTube conquered video. Facebook and Twitter conquered social media. Legacy newspapers just started posting their articles online. AOL could not lead the way anywhere, and it declined.

Moving on, Yahoo was one of the contenders for the best search engine in this same period, which some might remember, but it lost that battle to Google. In 2008, Microsoft offered to buy them for $44.6 billion, which the company flatly refused. After a period of rudderless management by multiple CEOs, it went into a nosedive, losing money and announcing massive layoffs.

Verizon acquired AOL for $4.1 billion in 2015 and Yahoo for $4.8 billion in 2017, merging them into Oath, Inc., which was later rebranded as Verizon Media Group. What exactly was the management of Verizon thinking at this time? In his 2015 and 2017 letters to shareholders, Verizon CEO Lowell McAdam wrote:

On the strategic front, we made a major move in the mobile media marketplace by acquiring AOL in June 2015. With AOL, we now have a highly sophisticated mobile advertising platform, as well as popular online content like the Huffington Post, Engadget and TechCrunch.

To ensure we take full advantage of this convergence of connectivity and content, Verizon has made some important strategic acquisitions. In 2017, we completed the purchase of the operating business of Yahoo, which significantly expands our content offerings – as well as the audience to which we can stream that content.

The telecom believed that it could be more than a telecom. It thought it could leverage its wireless infrastructure into a digital media empire that would run on its towers. AT&T had some similar thoughts in this period, with its purchase of companies like DirectTV and Warner Bros. Verizon had found recognizable brands that were limping and looking for buyers. They were easy prey.

Performance

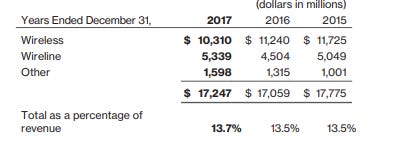

As we can see here from these snapshots of Verizon’s annual reports, their media group (which fall under “corporate and other”) did not show increasing revenues. With just under $10 billion in 2015, we don’t see much upward movement, and the media assets typically ranged 45% to 60% of corp/other segment’s revenues. While these numbers moved sideways, capex for their corp/other segments went up.

It’s difficult to know the exact cash they produced because of how it was reported, but the trends give us an idea that it was not going well. OCF for the year ending 2020, was $41.8 billion, a CAGR of only 1.45% from 2015 levels.

What Went Wrong?

Verizon committed cash and attention to mediocre companies. AOL and Yahoo were has-beens struggling to regain relevance. Verizon got them cheap, yes, at 10% of what Microsoft offered for Yahoo, but as Warren Buffett has said:

It’s far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.

Wonderful companies, even if you pay a bit more for them, have more growth and upside. Mediocre companies are more likely to go down. When Google bought YouTube, it was able to replace its own video service with something better, and YouTube could benefit from Google’s search algorithm. AOL and Yahoo did not give comparable advantages to Verizon. People were not flocking to AOL and Yahoo, and Verizon had to know that when it bought them.

The End Result

Verizon ultimately sold the combined Media Group to Apollo Global Management for just $4.3 billion. The business was renamed to Yahoo, and Verizon was allowed to keep a 10% interest in it. Nevertheless, they were down about $4.5 billion for all that effort. What else could they have done?

Even in 2015, management was discussing the importance of rising 5G technology. It currently has about $129 billion in debt, largely to finance capex for its 5G infrastructure. Spending on that could have been less debt for shareholders.

By that same token, the company could have also bought back its own shares. Given stock prices around the time of those acquisitions, about 213 million shares could have been acquired. With about 4.2 billion shares now, that would have increased holders’ positions just over 5%, while also making the annual dividend hike easier to finance over time.

Most importantly, though, this did not kill Verizon. The disappointing numbers were only a drop in the bucket compared to the cash from its telecom services. Fundamentally, Verizon a wonderful business, which is why even Buffett recently bought some. The wonderfuls can try an acquisition “for fun” and accept a modest loss.

Verizon is a good example of what Peter Lynch calls “diworsification,” where a successful company makes bad acquisitions, as opposed to focusing on its core business or doing buybacks. While hindsight is 20-20, the signs were there from the beginning, and Lynch wrote about this idea in 1990. The lesson is that whether you buy some stock or the whole business, you have to pay attention to what exactly it is that you buy. Otherwise, it’s better to stick to what you know.